Quantifying Quality

What does quality mean for your customer? A core tenet of the Lean Six Sigma project is empiricism, so it is necessary to articulate, and quantify exactly what customer means. The Critical to Quality (CTQ) tree is a useful tool and thinking exercise for developing quantifiable measures of quality. These become the basis for data collection in the Measure phase, but can also be useful as engineering specifications, and key performance indicators.

🧭 Navigation

What Is Quality, Precisely?

Lean Six Sigma (LSS) is a project management methodology used to improve the performance and efficiency of business and engineering processes. It combines the heuristics of the Toyota Production System with statistical process control from Motorola. An LSS project is divided in to 5 stages:

- Define the problem,

- Measure the current performance,

- Analyse root causes of the problem,

- Improve the system, and

- Control the process.

In the Define phase it is also necessary to articulate who the customer is of a process. In a previous post , I showed how to use the SIPOC tool in order identify the customer(s). Once identified, is is then necessary to speak with the customer in order to quantify what quality means to them.

The problem is, a customer might not always be clear or precise in what they mean. But, since LSS is based on empiricism, it is necessary to translate vague customer requirements in to quantifiable metrics. That way we can collect and scrutinise the data in the Measure and Analyse phases.

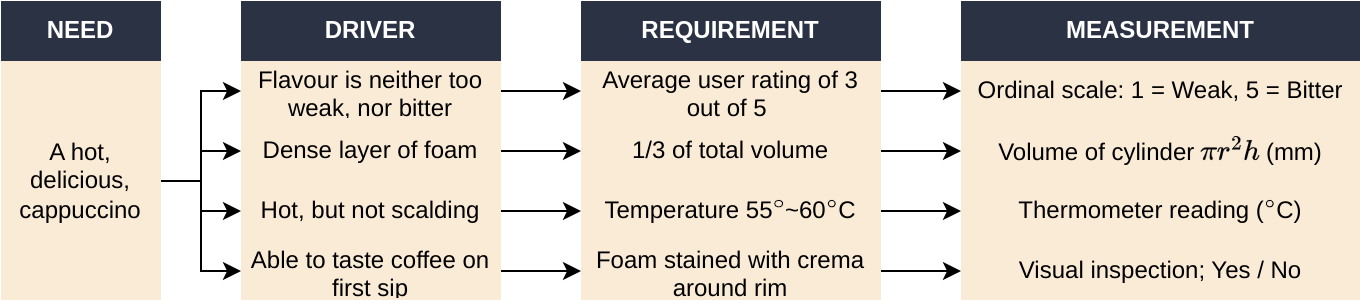

The Citical-To-Quality (CTQ) tree is a standard LSS tool used in the Define phase. It helps refine vague, or subjective notions about quality in to objective measurements.1

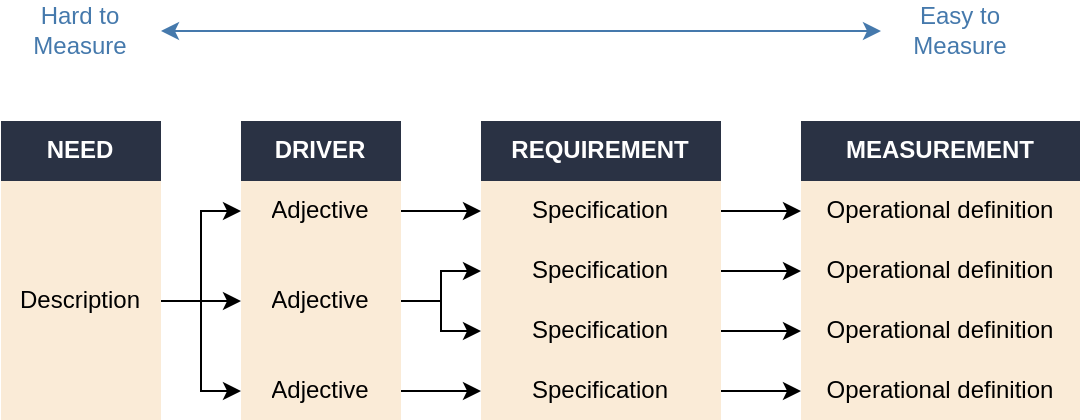

A CTQ tree contains 3 (or 4) components:

- What the customer needs,

- Drivers of quality,

- Requirements, or critical-to-quality-factors, and

- How the measurement is taken.

The structure of a CTQ tree.

Quality, Step-by-Step

1) Defining the Need

The first step is to provide a concise description of what the customer requires. It should be 1 sentence long, and ideally use adjectives to give a notion of quality factors. It should describe what quality is, but not how it is defined. Any lay person should have a basic understanding of what is being asked for.

Here are some bad examples I found on the internet, and what I think is a better definition:

| Original | My Definition |

|---|---|

| I need my paycheck. | A paycheck delivered regularly, on time, in the correct amount. |

| Ease of operation and maintenance. | Consistent operation with minimal defects & breakdowns. |

| Effective maintenance with minimal downtime. | |

| Monthly project report. | A timely monthly report with sufficient information on progress. |

Notice that all these examples don’t give adequate descriptors from which to build upon. The “Need” should be a counter-factual to an existing problem (hence why an LSS project is being undertaken). For example, “A monthly project report” could simply be an A4 paper, with a single sentence “All good.”, delivered any time within a 4 week period. But if the problem is that project reports are constantly late, and lacking detail, then the need should describe the converse: timely, and with sufficient information on progress.

2) Elaborating quality drivers

The next step is to list what quality entails. These should be adjectives. It can be difficult for people to start jumping to numerical quantities, so using descriptive words helps build momentum. A useful thing to ask is what does good look like?. Conversely, if you’re having trouble coming up with ideas, a better question to ask is what does bad look like?.

In a previous post, I mentioned a poor experience I had at a hotel. Below are some examples of turning a bad experience in to a performance requirement:

- Tepid water in the shower $\longrightarrow$ How water consistently available in the bathroom.

- Having to turn the tap really hard to stop water flowing $\longrightarrow$ Faucet can be turned off with minimal effort.

- Coffee is weak and watery $\longrightarrow$ Espresso available for breakfast.

3) Defining performance requirements

The next step is to turn these descriptions in to quantifiable metrics. This should give a precise number with some kind of constraint, preferably with a mathematical qualifier $=, >, <$. Continuing my example from above we could define:

- How water consistently available in the bathroom $\longrightarrow$ Water reaches 50 $^\circ$ C.

- Faucet can be turned off with minimal effort $\longrightarrow$ Water stops flowing between 0.5 Nm ~ 2 Nm

- Espresso available for breakfast $\longrightarrow$ Yes / No.

4) Define operational measurements

It’s often good to define how the measurement should be taken. This way we can:

- Agree that everyone is measuring the same thing, and

- Different people will measure consistently.

In the Define phase, this operational definition only needs to be high-level. If a more detailed procedure is necessary, it can be elaborated on in the Measure phase as part of the data collection plan.

- Water reaches 50 $^\circ$ C $\longrightarrow$ Take temperature of water withing 1cm of the shower head with a thermometer.

- Water stops flowing between 0.5 Nm ~ 2 Nm $\longrightarrow$ Use a torque wrench set to 2 Nm.

Examples

Lamingtons

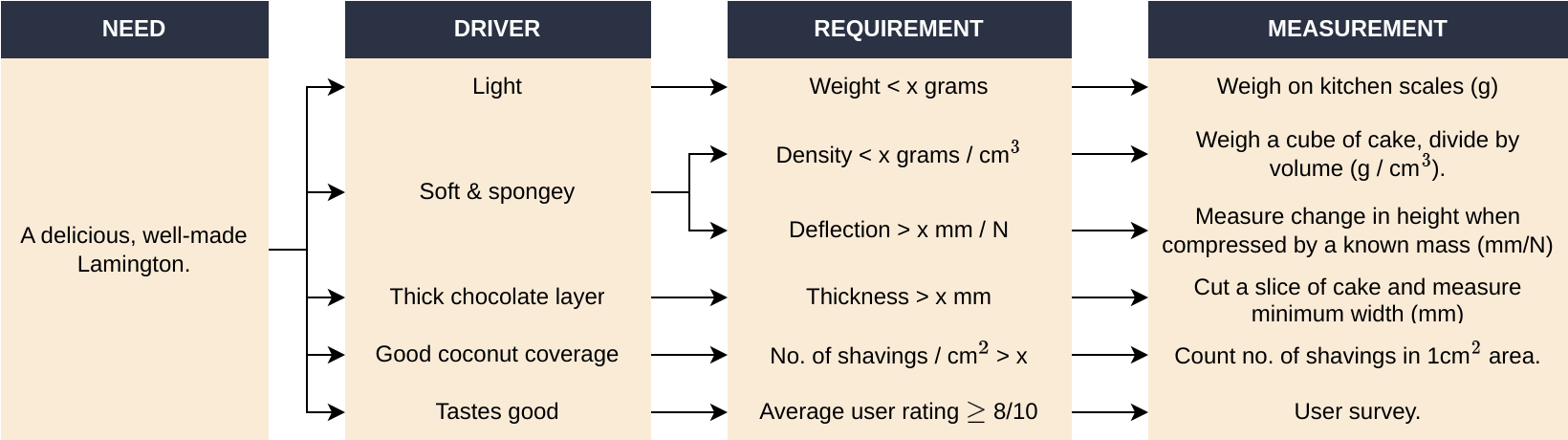

In a previous post I used an example of the time I made lamingtons for friends and colleagues whilst I was living in Italy. These are an Australian delicacy, consisting of a sponge cake, dipped in chocolate sauce, and rolled in coconut shavings. I developed a SIPOC, which is a tool used to identify who receives the output of a process, i.e. the customer. Then based on customer feedback, we can proceed with developing the CTQ tree.

Delicious lamingtons, made by me!

One of the problems I had was that my first batch was perfect, and all subsequent batches were too dense and flat. Below is how a CTQ tree might be developed for making good lamingtons:

A CTQ tree for properly made lamingtons.

On my first batch (where the sponge cake quality was perfect), the chocolate layer was quite thick. I thought it was too much, but my friend said it was perfect. She didn’t like that commercially made lamingtons have thin chocolate layers in order to save money. This highlights the necessity of getting direct customer feedback when creating the CTQs (thanks Trina!).

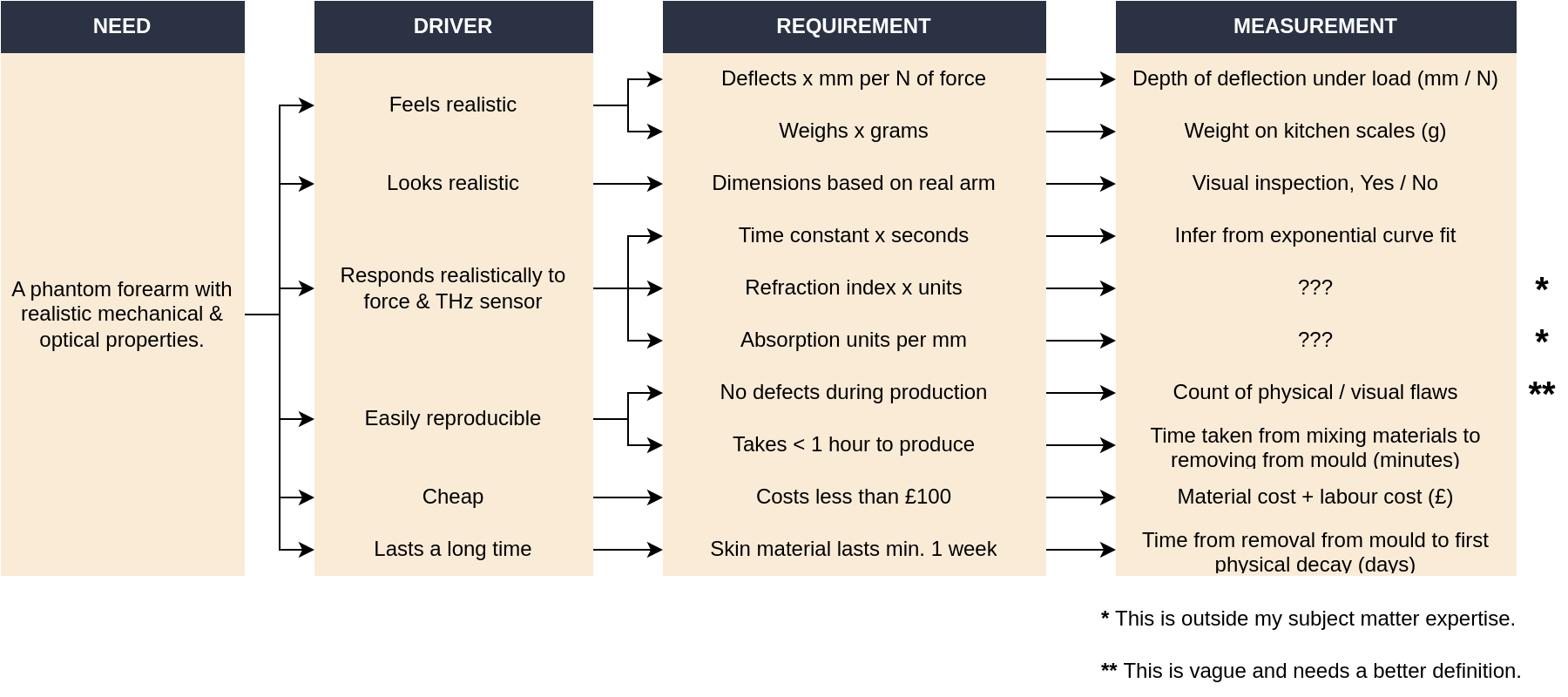

Medical Phantom Organ

Whilst working on the Terabotics project with the University of Leeds, other postdocs and I won a competition for our mini research proposal. The idea was to make artificial limbs with the same optical and mechanical properties as a human (a phantom limb / organ). It could be used for testing and experiments using THz sensing in skin contact measurements.

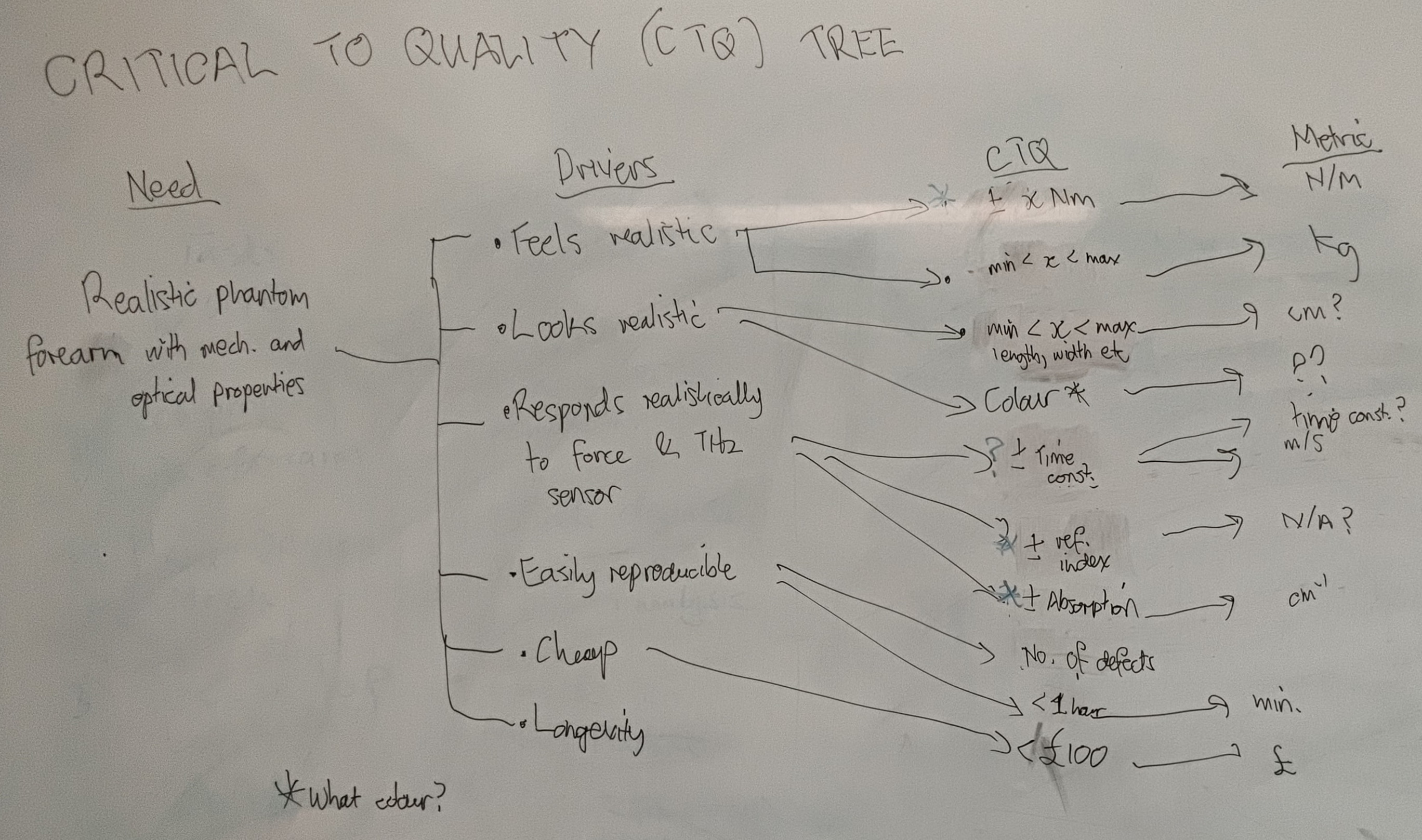

In late 2024, we met at the University of Warwick for a workshop to develop a plan for how we were going to make these things. It had never been done before (phantom organs exist, but not phantom limbs for this specific technology), so the CTQ tree was the perfect tool to take a vague definition and refine it into quantitative engineering specifications.

Below is the initial draft we developed, and below is my refined version.

A CTQ tree to define engineering specifications of a phantom forearm for skin contact sensing.

One of the interesting outcomes from applying this tool was that, during discussions, we realized the compression of the skin decays asymptotically over time. This can be quantified using a mathematical property called a time constant. The process of developing the tool itself helped us articulate and define this important metric.

Another thing to note is, the first draft we developed (pictured above) had a few question marks, uncertainties, and deficiencies. It can be difficult to get produce a correct CTQ on the first go. After some thought, and reflection, I developed a better one. It should be standard practice to take some extra time to ensure the metrics are correctly defined. This will have a big impact on what data is collected during the Measure phase. Conversely, it’s also OK to get things wrong, and go back and change it as necessary.

Customer vs Process

From about 2006 to early 2007, I worked as a barista. I became quite skilled at making coffee, and I had a very strict process. The proof of my efforts was the reputation I developed for making excellent quality coffee.

A cappuccino I made working as a barista in 2007.

Making good coffee is surprisingly technical. For example:

- The extraction time for the crema must be within 24 to 26 seconds.

- $<$ 24 seconds, and the coffee is too weak.

- $>$ 26 seconds, and the coffee is too bitter.

- The milk has to be heated to a maximum of 60 $^\circ$ C. If it gets too hot, the fat melts, and you can’t generate good foam.

- Humidity affects the extraction time, and you have to adjust the grind size, and tamping force throughout the day.

- You need to pour the milk on to the crema immediately, otherwise it start losing flavour.

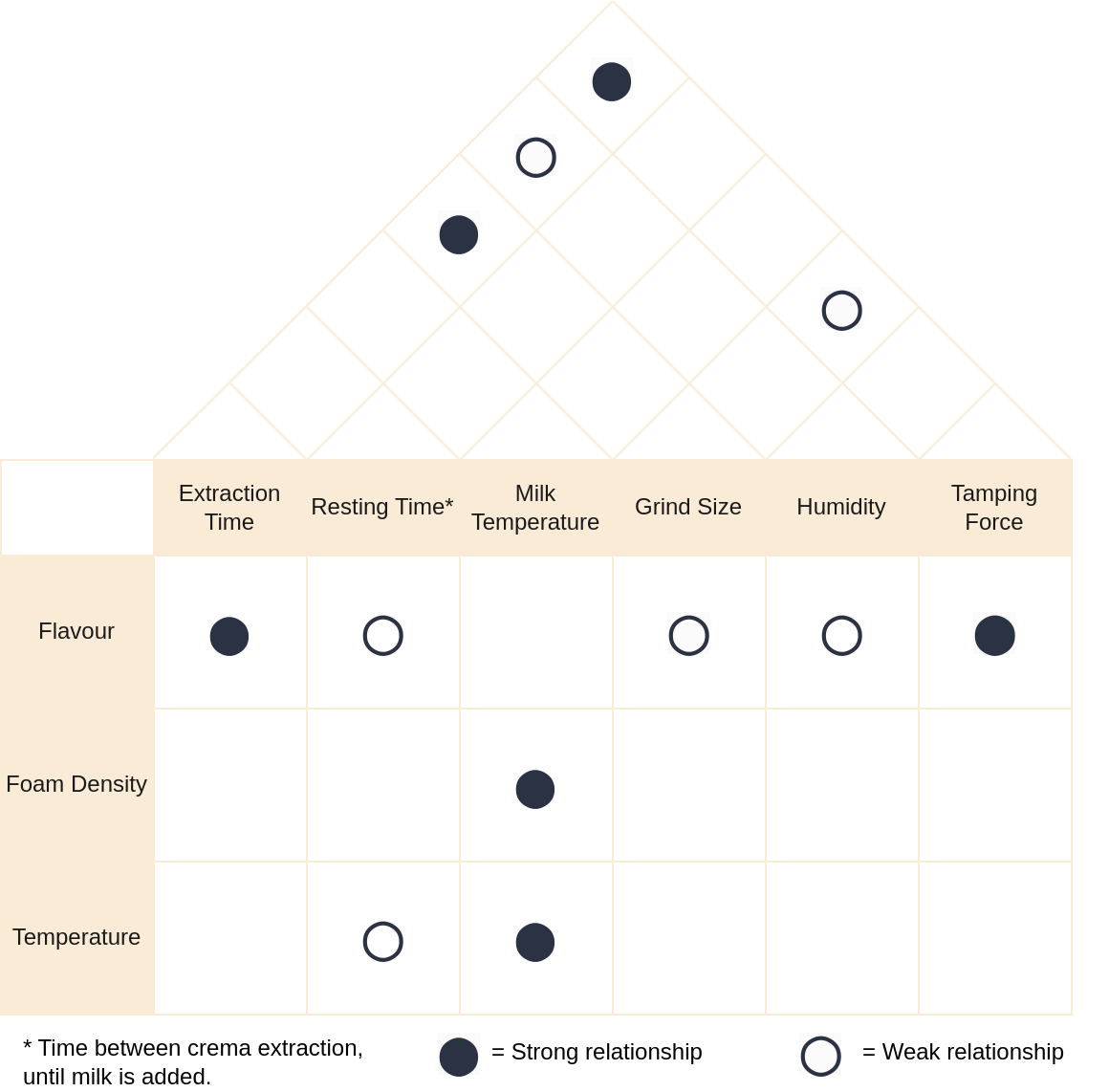

A CTQ tree is developed based on customer requirements, but how we achieve those requirements internally might be different. In this case, it is necessary to use tools like the quality function deployment (QFD) that maps the relationship between what the customer wants (i.e. the CTQs), versus how to achieve it internally within the process.

For example, here is a customer-centric CTQ of what makes a good cappucino:

A CTQ tree for a cappuccino.

But based on my expert knowledge above, here is the QFD that relates the quality factors for a good coffee to the technical aspects involved in making it. Notice that there are multiple factors that affect the flavour, and, from a production side, many of them are interrelated (as seen in the “roof” part of the diagram).

A matrix diagram, or quality function deployment (QFD), relating customer requirements to technical specifications for coffee production.

The customer doesn’t care about technical details like extraction time, the precise temperature measurements, etc. They only care that the coffee tastes good, is well made, and is sufficiently hot. But in order to meet this customer expectations, the actual coffee making process must be very tightly controlled.

Key Takeaway

The Critical to Quality Tree is a useful tool and structued thinking exercise for translating vague, subjective customer needs in to quantifiable performance metrics. These become the basis for developing a data collection plan in the the Measure phase of the project. A well thought-out CTQ tree can provide useful KPIs for a business or product.

Some of the important things I’ve learned over the years is to:

- Have a short, but descriptive need. It should convey basic descriptors of quality, without saying too much.

- Quality drivers are subjective, they should involve adjectives.

- It’s helpful to pose a question when developing drivers: “What does good look like?”, or “What does bad look like?”.

- The requirements, or CTQs, must have a quantifiable metric attached, and some sort of constraint $=, >, <$ where possible.

- It’s useful to provide an operation definition for how a measurement is taken.

-

The Tree Diagram is one of the 7 Management & Planning Tools. ↩