Quaternions for Dummies

Quaternions are sophisticated mathematical objects that are used to represent orientation in 3D for robotics, animation, and aerospace. In this article I trace a logical sequence from using complex numbers as rotations toward the derivation of the quaternion itself. I then derive the Lie group properties for combining and inverting quaternions. Lastly, I show how they can be used to rotate vectors, and some of their advantages over rotation matrices.

🧭 Navigation

- Complex Numbers as Rotations

- Complex Numbers in Higher Dimensions?

- Hamilton’s Epiphany

- Advantages of Quaternions

Complex Numbers as Rotations

Euler’s formula states that:

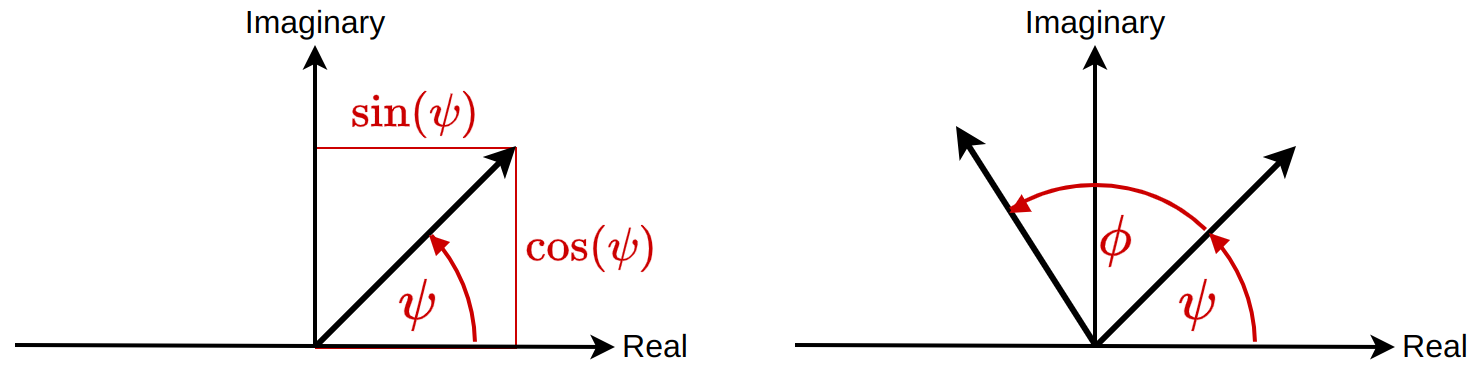

\[e^{i\psi} = \cos(\psi) + i\cdot\sin(\psi) \in\mathbb{C} ~,~ i = \sqrt{-1}. \tag{1}\]We can think of this as a rotation in to the complex plane (Fig. 1). When we multiply powers together, we add the exponent. This equates to adding rotations together (Fig. 1):

\[e^{i\psi}\cdot e^{i\phi} = e^{i(\psi + \phi)} = \cos(\psi + \phi) + i\cdot\sin(\psi + \phi). \tag{2}\]

Figure 1: A complex number represents a rotation in to the complex plane. Multiplying complex numbers is equivalent to adding rotations.

If we took a complex number:

\[\mathrm{z} = \mathrm{x} + i\cdot\mathrm{y}\in\mathbb{C} \tag{3}\]and multiplied it by Eqn. (1) then we would get:

\[\begin{align} e^{i\psi}\cdot \mathrm{z} &= \left(\cos(\psi) + i\cdot\sin(\psi)\right)\left(\mathrm{x} +i\cdot \mathrm{y}\right) \tag{4a} \\ &= \mathrm{x}\cdot\cos(\psi) - \mathrm{y}\cdot\sin(\psi) + i\left(\mathrm{x}\cdot\sin(\psi) - \mathrm{y}\cdot\cos(\psi)\right) \tag{4b} \end{align}\]But we could also represent Eqn. (3) as a vector:

\[\mathbf{v} = \begin{bmatrix} \mathrm{x} \\ \mathrm{y} \end{bmatrix} \begin{matrix} \leftarrow \text{Real part}\phantom{abcd} \\ \leftarrow \text{Complex part} \tag{5} \end{matrix}\]In the same manner, we could write Eqn. (4) as:

\[\begin{bmatrix} \mathrm{x}\cdot\cos(\psi) - \mathrm{y}\cdot\sin(\psi) \\ \mathrm{x}\cdot\sin(\psi) + \mathrm{y}\cdot\cos(\psi) \end{bmatrix} = \underbrace{ \begin{bmatrix} \cos(\psi) & -\sin(\psi) \\ \sin(\psi) & \phantom{-}\cos(\psi) \end{bmatrix} }_{\mathbf{R}} \underbrace{ \begin{bmatrix} \mathrm{x} \\ \mathrm{y} \end{bmatrix} }_{\mathbf{v}}. \tag{6}\]This matrix $\mathbf{R}$ is in fact a 2D rotation matrix. It belongs to the Special Orthogonal group:

\[\mathbb{SO}(n) = \left\{ \mathbf{R}\in\mathbb{R}^{n\times n} ~\big|~ \mathbf{RR}^T = \mathbf{I}~,~ det(\mathbf{R}) = 1 \right\}. \tag{7}\]Multiplying a complex number by Euler’s equation is equivalent to rotating a 2D vector with a 2D rotation matrix. But this isn’t the only connection between complex numbers and 2D rotations. An eigenvector $\mathbf{v}$ of $\mathbf{R}\in\mathbb{SO}(2)$ satisfies the identity:

\[\mathbf{Rv} = \lambda\mathbf{v} \tag{8}\]where $\lambda$ is the corresponding eigenvalue. We can find the eigenvalue(s) of a 2D matrix using the shortcut:

\[\begin{align} \lambda^2 - trace(\mathbf{R}) \lambda + det(\mathbf{R}) &= 0 \tag{9a} \\ \lambda^2 -2\cos(\psi) + 1&= 0 \tag{9b} \end{align}\]where

- $trace(\cdot)$ is the sum of diagonal elements, and

- $det(\cdot)$ is the determinant.

We can then solve Eqn. (9) with the quadratic formula and some trigonometric identities:

\[\begin{align} \lambda = \cos(\psi) &\pm \sqrt{\cos^2(\psi)-1 } \tag{10a}\\ \cos(\psi) &\pm \sqrt{-\sin^2(\psi)} \tag{10b} \\ \cos(\psi) &\pm i\cdot\sin(\psi) \in\mathbb{C}. \tag{10c} \end{align}\]The eigenvalue of $\mathbb{SO}(2)$ is a complex number. Is this surprising? Take a look at Eqn. (4), (6) and (8) again:

\[e^{i\psi}\cdot \mathrm{z} = \lambda\mathbf{v} = \mathbf{R}\mathbf{v}. \tag{11}\]Complex Numbers in Higher Dimensions?

Now you may be thinking: if 1 complex element gives rotation in 2D, then 2 complex elements are needed for rotation in 3D. Let’s declare an “extended” complex number where $j = \sqrt{-1}$:

\[\mathrm{x} + i\cdot \mathrm{y} + j \cdot \mathrm{z} \in\mathbb{C}^2. \tag{12}\]What happens when we multiply two of them together?

\[\begin{align} \left(\mathrm{x} + i\cdot \mathrm{y} + j\cdot \mathrm{z}\right)\left(\mathrm{x} + i\cdot \mathrm{y} + j\cdot \mathrm{z}\right) &= \underbrace{\mathrm{x}^2 - \mathrm{y}^2 - \mathrm{z}^2}_{\text{Real}} + \underbrace{i\cdot 2\mathrm{xy} + j\cdot 2\mathrm{xz}}_{\text{Complex}} + \underbrace{\left(ij + ji\right)\cdot \mathrm{yz} }_{\text{???}} \notin\mathbb{C}^2 \tag{13} \end{align}\]What is $ij$ and $ji$? The mathematical object on the right is different from the object on the left. The problem is that Eqn. (12) is not a Lie group.

Lie groups are mathematical objects that satisfy 4 properties:

- Closure: Combining 2 elements within the group produces another element within the group.

- Associativity: The manner in which we cluster a series of closure operations doesn’t matter, as long as the sequence remains the same.

- Identity: The element that results in no change.

- Inverse: The element that leads to the identity.

Complex numbers form a Lie group. This why we could rotate another complex number using Eqn. (4). We multiply 2 complex numbers, and get a 3rd. Equation (13) violates the closure property. To represent rotations in 3D, we need a Lie group so that we can use the closure property to combine them.

| Group Properties of $\mathbb{C}$ (Over Multiplication) | |

|---|---|

| Closure: | $\mathrm{z}_1,\mathrm{z}_2\in\mathbb{C}~:~ \mathrm{z}_1 \mathrm{z}_2 \in\mathbb{C}$ |

| Associativity: | $\left(\mathrm{z}_1 \mathrm{z}_2\right) \mathrm{z}_3 = \mathrm{z}_1 \left(\mathrm{z}_2 \mathrm{z}_3\right)$ |

| Identity: | $1 \equiv1+i\cdot0\subset\mathbb{C}: 1\mathrm{z} = \mathrm{z}$ |

| Inverse: | $\mathrm{z}^{-1} = \frac{\bar{\mathrm{z}}}{\mathrm{z}\bar{\mathrm{z}}} ~:~ \mathrm{z}^{-1}\mathrm{z} = 1 + i\cdot 0$ |

Hamilton’s Epiphany

Sir William Rowan Hamilton proposed the now famous quaternion:

\[\boldsymbol{q} = \mathrm{w} + i\cdot \mathrm{x} + j\cdot \mathrm{y} + k\cdot \mathrm{z} \in\mathbb{H} \tag{14}\]where $i^2 = j^2 = k^2 = \sqrt{-1}$. By multiplying 2 of them together with standard rules for arithmetic we obtain:

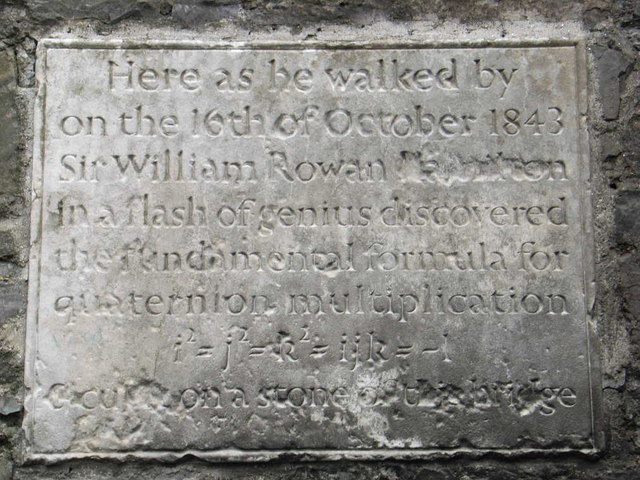

\[\begin{align} \boldsymbol{q}_1\cdot\boldsymbol{q}_2 &= (\mathrm{w}_1\mathrm{w}_2 - \mathrm{x}_1\mathrm{x}_2 - \mathrm{y}_1\mathrm{y}_2 -\mathrm{z}_1\mathrm{z}_2) \nonumber \\ &+ i\cdot(\mathrm{w}_1 \mathrm{x}_2 + \mathrm{x}_1 \mathrm{w}_2) + j\cdot(\mathrm{w}_1 \mathrm{y}_2 + \mathrm{y}_1 \mathrm{w}_2) + k\cdot(\mathrm{w}_1 \mathrm{z}_2 + \mathrm{z}_1 \mathrm{w}_2) \nonumber \\ &+ ij\cdot\mathrm{x}_1\mathrm{y}_2 + ji\cdot\mathrm{y}_1\mathrm{x}_2 + jk\cdot\mathrm{y}_1\mathrm{z}_2 + kj\cdot\mathrm{z}_1\mathrm{y}_2 + ki\cdot\mathrm{z}_1\mathrm{x}_2 + ik\cdot\mathrm{x}_1\mathrm{z}_2. \tag{15} \end{align}\]On October 16th, 1843, he had an epiphany about how to resolve the closure property. His insight was to say that $ijk = -1$. He inscribed this now famous identity on to the Brougham Bridge in Dublin (Fig. 2).

Figure 2: A plaque on Brougham (Broom) Bridge commemorating Hamilton's invention.

(JP, William Rowan Hamilton Plaque, CC BY-SA 2.0)

| Quaternion | Multiplication | Rules | |

|---|---|---|---|

| $\times$ | $\phantom{-}i$ | $\phantom{-}j$ | $\phantom{-}k$ |

| $i$ | $-1$ | $\phantom{-}k$ | $-j$ |

| $j$ | $-k$ | $-1$ | $\phantom{-}i$ |

| $k$ | $\phantom{-}j$ | $-i$ | $-1$ |

The key is that quaternions obey their own rules for multiplication. Specifically, we resolve $ij = k$, $ji = -k$, etc. That way $ijk = k^2 = -1$. We may now complete Eqn. (15):

\[\begin{align} \boldsymbol{q}_1\cdot\boldsymbol{q}_2 &= \phantom{h\cdot}(\mathrm{w}_1\mathrm{w}_2 - \mathrm{x}_1\mathrm{x}_2 - \mathrm{y}_1\mathrm{y}_2 -\mathrm{z}_1\mathrm{z}_2) \nonumber \\ &+ i\cdot(\mathrm{w}_1 \mathrm{x}_2 + \mathrm{x}_1 \mathrm{w}_2 + \mathrm{y}_1\mathrm{z}_2 - \mathrm{z}_1\mathrm{y}_2) \nonumber\\ &+ j\cdot(\mathrm{w}_1 \mathrm{y}_2 + \mathrm{y}_1 \mathrm{w}_2 + \mathrm{z}_1\mathrm{x}_2 - \mathrm{x}_1\mathrm{z}_2 ) \nonumber \\ &+ k\cdot(\mathrm{w}_1 \mathrm{z}_2 + \mathrm{z}_1 \mathrm{w}_2 + \mathrm{x}_1\mathrm{y}_2 - \mathrm{y}_1\mathrm{x}_2) \in\mathbb{H} \tag{16} \end{align}\]which satisfies the closure property for a Lie group.

If the exponential of a purely imaginary complex number represents a rotation, Eqn. (1), what about a purely complex quaternion?

\[\boldsymbol{p} = i\cdot\mathrm{x} + j\cdot\mathrm{y} + k\cdot\mathrm{z} \in\mathbb{H}. \tag{17}\]When exponentiating Eqn. (17) we obtain:

\[e^{\boldsymbol{p}} = \sum_{n=0}^{\infty} \frac{(\|\boldsymbol{p}\|\cdot\hat{\boldsymbol{p}})^n} {n!} \tag{18}\]where $\hat{\boldsymbol{p}} = \frac{\boldsymbol{p}}{|\boldsymbol{p}|}$ such that $\hat{\boldsymbol{p}}^2 = -1$. We can split this in to even and odd terms and simplify them a little:

\[\begin{align} (\|\boldsymbol{p}\|\cdot\hat{\boldsymbol{p}})^{2n\phantom{+1}} &= (-1)^n \cdot\|\boldsymbol{p}\|^{2n} \tag{19a} \\ (\|\boldsymbol{p}\|\cdot\hat{\boldsymbol{p}})^{2n+1} &= (-1)^n \cdot\|\boldsymbol{p}\|^{2n+1} \cdot \hat{\boldsymbol{p}}. \tag{19b} \end{align}\]By substituting Eqn. (19a) & (19b) in to (18) we arrive at:

\[e^{\boldsymbol{p}} = \underbrace{\sum_{n=0}^{\infty} \frac{(-1)^n \cdot\|\boldsymbol{p}\|^{2n}} {(2n)!}}_{\cos(\|\boldsymbol{p}\|)} + \underbrace{\sum_{n=0}^{\infty} \frac{(-1)^n \cdot\|\boldsymbol{p}\|^{2n+1}} {(2n+1)!}}_{_{\sin(\|\boldsymbol{p}\|)}}\cdot\hat{\boldsymbol{p}} \in\mathbb{H} \tag{20}\]which is itself a quaternion. In this context,

- $|\boldsymbol{p}|$ is equivalent to the magnitude of rotation, and

- $\hat{\boldsymbol{p}}$ is the axis of rotation.

This is exactly what Euler’s rotation theorem states: any 3D rotation may be parameterised by an angle of rotation about a fixed axis. Thus, we can use quaternions to represent rotation. But not just any quaternion; it must be the exponential of a purely imaginary quaternion.

Euler-Rodrigues Parameters & The Versor

I am now going to switch notation, and from (14) I am going to define:

\[\eta = \mathrm{w} ~,~ \boldsymbol{\varepsilon} = \begin{bmatrix} \mathrm{x} \\ \mathrm{y} \\ \mathrm{z} \end{bmatrix} ~\longrightarrow~ \boldsymbol{q} = \begin{bmatrix} \eta \\ \boldsymbol{\varepsilon} \end{bmatrix}. \tag{21}\]From careful inspection of Eqn. (16) we can now re-write the product of 2 quaternions using 2 familiar vector operations; the dot product1, and cross product:

\[\boldsymbol{q}_1 \cdot \boldsymbol{q}_2 = \begin{bmatrix} \eta_1\eta_2 - \boldsymbol{\varepsilon}_1^T\boldsymbol{\varepsilon}_2 \\ \eta_1 \boldsymbol{\varepsilon}_2 + \eta_2\boldsymbol{\varepsilon}_1 + \boldsymbol{\varepsilon}_1\times\boldsymbol{\varepsilon}_2 \end{bmatrix} \in\mathbb{H}. \tag{22}\]To re-iterate, this is the closure property of $\mathbb{H}$. In fact, if the product of any 2 quaternions is another quaternion, then the associativity property follows:

\[\left(\boldsymbol{q}_1 \cdot \boldsymbol{q}_2\right) \cdot \boldsymbol{q}_3 = \boldsymbol{q}_1 \cdot \left(\boldsymbol{q}_2 \cdot \boldsymbol{q}_3\right). \tag{23}\]Be careful though; since $\boldsymbol{\varepsilon}_1\times\boldsymbol{\varepsilon}_2 \ne \boldsymbol{\varepsilon}_2\times\boldsymbol{\varepsilon}_2$ it is also the case that $\boldsymbol{q}_1\cdot\boldsymbol{q}_2 \ne \boldsymbol{q}_2\cdot\boldsymbol{q}_1$.

The identity element of a quaternion is the same as $\mathbb{C}$, a unit real part and zero complex part:

\[\boldsymbol{\iota} = \begin{bmatrix} 1 \\ \mathbf{0} \end{bmatrix} \in\mathbb{H}~\Longrightarrow ~ \boldsymbol{q}\cdot\boldsymbol{\iota} = \boldsymbol{q}. \tag{24}\]Now, for a complex number we obtain the conjugate by negating the complex component. The product of a complex number and its conjugate gives a purely real number:

\[\mathrm{z} = \mathrm{x} + i\cdot\mathrm{y}~,~\bar{\mathrm{z}} = \mathrm{x} - i\cdot\mathrm{y} \in\mathbb{C} ~\Longrightarrow~ \mathrm{z\bar{z}} = \mathrm{x}^2 + \mathrm{y}^2 \in\mathbb{R}. \tag{25}\]The same is true of quaternions. We form the conjugate by negating the complex component. And when we multiply a quaternion with its conjugate we end up with a purely real number:

\[\bar{\boldsymbol{q}} = \begin{bmatrix} \phantom{-}\eta \\ -\boldsymbol{\varepsilon} \end{bmatrix} ~\Longrightarrow~ \boldsymbol{q}\cdot\bar{\boldsymbol{q}} = \begin{bmatrix} \eta^2 + \boldsymbol{\varepsilon}^T\boldsymbol{\varepsilon} \\ \mathbf{0} \end{bmatrix}. \tag{26}\]Can you see it? Eqn. (26) leads to the identity Eqn. (24) if, and only if:

\[\underbrace{\eta^2 + \boldsymbol{\varepsilon}^T\boldsymbol{\varepsilon}}_{\mathrm{w^2 + x^2 + y^2 + z^2}} = 1. \tag{27}\]This condition is known as the Euler-Rodrigues parameters. We already have a solution using the exponential quaternion Eqn. (20):

\[\boldsymbol{v} =e^{\tfrac{1}{2}\mathbf{a}} = \underbrace{\cos\left(\tfrac{1}{2}\alpha\right)}_{\eta} + \underbrace{\sin\left(\tfrac{1}{2}\alpha\right)\hat{\mathbf{a}}}_{\boldsymbol{\varepsilon}} \in \mathbb{S}^3\subset \mathbb{H} \tag{28}\]where $\mathbf{a} = \alpha\cdot\hat{\mathbf{a}}$ (the angle-axis parameterisation). The reason for the half angle will be apparent later. A quaternion of unit norm is called a versor. Equation (27) implies that the versor is a point on the surface of a 4D sphere, hence $\mathbb{S}^3$ (4D volume, 3D surface).

So for a versor, the conjugate is the inverse element since:

\[\boldsymbol{v}\cdot\bar{\boldsymbol{v}} = \boldsymbol{\iota}. \tag{29}\]We have completed the Lie algebra; but not for quaternions $\mathbb{H}$ per se, but for versors $\mathbb{S}^3\subset\mathbb{H}$.

| Group Properties for $\mathbb{S}^3\subset\mathbb{H}$ | |

|---|---|

| Closure: | $\boldsymbol{v}_1,\boldsymbol{v}_2\in\mathbb{S}^3~:~\boldsymbol{v}_1\cdot\boldsymbol{v}_2\in\mathbb{S}^3$ |

| Associativity: | $\left(\boldsymbol{v}_1\cdot\boldsymbol{v}_2\right)\cdot\boldsymbol{v}_3 = \boldsymbol{v}_1\cdot\left(\boldsymbol{v}_2\cdot\boldsymbol{v}_3\right)$ |

| Identity: | $\boldsymbol{\iota} = \begin{bmatrix} 1 & \mathbf{0} \end{bmatrix}^T\in\mathbb{S}^3 ~:~ \boldsymbol{v}\cdot\boldsymbol{\iota} = \boldsymbol{v}$ |

| Inverse: | $\bar{\boldsymbol{v}} = \begin{bmatrix} \eta & -\boldsymbol{\varepsilon}^T\end{bmatrix}^T~:~ \boldsymbol{v}\cdot\bar{\boldsymbol{v}} = \boldsymbol{\iota}$ |

Rotating Vectors

To rotate a vector $\mathbf{v}\in\mathbb{R}^3$ we:

- Treat it as a pure quaternion, and

- Couch it between a versor $\boldsymbol{v}\in\mathbb{S}^3$ and its conjugate $\bar{\boldsymbol{v}}$.

The result is:

\[\begin{bmatrix} 0 \\ \mathbf{u} \end{bmatrix} = \overbrace{ \begin{bmatrix} \eta \\ \boldsymbol{\varepsilon} \end{bmatrix} }^{\boldsymbol{v}} \cdot \begin{bmatrix} 0 \\ \mathbf{v} \end{bmatrix} \cdot \overbrace{ \begin{bmatrix} \phantom{-}\eta \\ -\boldsymbol{\varepsilon} \end{bmatrix} }^{\bar{\boldsymbol{v}}} = \begin{bmatrix} 0 \\ \mathbf{R}(\eta,\boldsymbol{\varepsilon})\mathbf{v} \end{bmatrix}. \tag{30}\]First, we need the half-angle in Eqn. (28) so that, when we apply this left-side and right-side product, we end up with zero in the real part of the result. Without it, we wouldn’t have a pure quaternion (try it!).

Second, any rotation of a vector $\mathbf{v}\in\mathbb{R}^n \to \mathbf{u}\in\mathbb{R}^n$ that preserves its length is equivalent to applying a rotation matrix $\mathbf{R}\in\mathbb{SO}(n)$. If we were to expand Eqn. (30) we would find:

\[\mathbf{R}(\eta,\boldsymbol{\varepsilon}) = \begin{bmatrix} 1 - 2(\varepsilon_2^2 + \varepsilon_3^2) & 2(\varepsilon_1 \varepsilon_2 - \eta \varepsilon_3) & 2(\varepsilon_1 \varepsilon_3 + \eta \varepsilon_2) \\ 2(\varepsilon_1 \varepsilon_2 + \eta \varepsilon_3) & 1 - 2(\varepsilon_1^2 + \varepsilon_3^2) & 2(\varepsilon_2 \varepsilon_3 - \eta \varepsilon_1) \\ 2(\varepsilon_1 \varepsilon_3 - \eta \varepsilon_2) & 2(\varepsilon_2 \varepsilon_3 + \eta \varepsilon_1) & 1 - 2(\varepsilon_1^2 + \varepsilon_2^2) \end{bmatrix}\in\mathbb{SO}(3) \tag{31}\]Now we have a short-hand for constructing a rotation matrix from a versor. This is more efficient because we can skip all the calculations that cancel to zero.

NOTE: $\boldsymbol{v}$ and $-\boldsymbol{v}$ represent the same orientation. This is because $\mathbf{u} = (-\boldsymbol{v})\cdot\mathbf{v}\cdot(-\bar{\boldsymbol{v}}) = \boldsymbol{v}\cdot\mathbf{v}\cdot\bar{\boldsymbol{v}}$. You can think of it like this: facing South and walking backwards is equivalent to facing North and walking forwards.

Advantages of Quaternions

Quaternions are used in animation, robotics, and aerospace. They require fewer floating point operations (FLOPs) when propagating rotations versus rotation matrices. However, they are more costly when rotating vectors. This can be reduced from 56 flops to 39 flops by forming a rotation matrix first, Eqn. (31), then performing the rotation.

Quaternions are also much more efficient for storing and transmitting data. They only require 4 parameters, versus 9 for rotation matrices. This is important when we have limited bandwidth, and limited storage space.

They are also numerically stable. Successive rotations will lead to an accumulation of floating point error. We can easily re-normalise a versor to preserve Eqn. (27).

| $\mathbb{SO}(3)$ | $\mathbb{S}^3\subset\mathbb{H}$ | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Parameters | 9 | 4 | |

| Closure | Multiplications | 27 | 16 |

| Additions | 18 | 12 | |

| Total FLOPs | 45 | 28 | |

| Vector Rotation | Multiplications | 9 | 32 (23) |

| Additions | 6 | 24 (16) | |

| Total FLOPs | 15 | 56 (39) |

-

For two vectors $\mathbf{a},\mathbf{b}\in\mathbb{R}^n$ the dot product $\mathbf{a}\bullet\mathbf{b} = \mathbf{a}^T\mathbf{b}$. ↩